PinS and the CAA Needles (Verb or Noun, You Be the Judge...)!

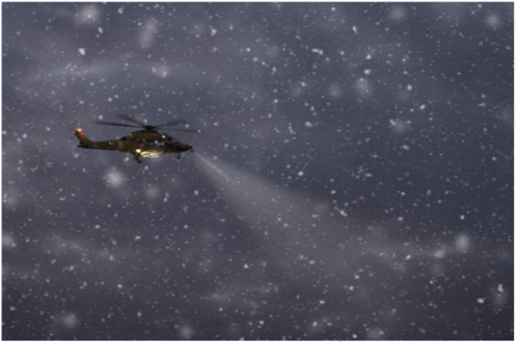

If only there were procedures that could enable HEMS operations in adverse weather conditions...

Image: helicopter: Susan Reed; weather vane © brankica | VectorStock; clouds: © nd700 | Adobe Stock

Looking out of my lounge windows on this cold, overcast day with low clouds scudding along, I see the local HEMS 169 AW as it flies over my house - obviously returning from an emergency call-out and now en route back to its base at the small GA airfield just a couple of miles north of where I live. Certainly not a great day for flying and, as the weather deteriorates and evening approaches, it becomes obvious that it will not be long before the local HEMS operations will be suspended for the day[1]. This must be very frustrating for a service dedicated to responding rapidly to serious trauma emergencies, providing much-needed rapid transfer to the 'right' facility, so critical to a patient's survival and recovery rate. If only there were procedures that could enable HEMS operations in adverse weather conditions, in turn, enabling the delivery of life-saving treatment in the so-called 'golden hour' (i.e. the hour immediately following a serious injury)... hang on a minute...

Of course, those that follow our blogs will know that such procedures do exist! Known as Point in Space procedures (PinS), they are already widely deployed throughout Europe, yet are all but absent in the UK. Why the imbalance? Several of our readers have asked us to offer further detail on the reasons why UK HEMS operations are being constrained by weather when this is not the case in other countries; we have alluded to some of the reasons in previous blogs, so please humour us as we discuss PinS again.

To recap briefly: PinS are GNSS-based procedures designed for helicopters only and can be a key enabler for the delivery of helicopter-borne patients to critical care facilities in adverse conditions. The operational feasibility of PinS has been proven and they offer clear (aviation) safety and community/societal benefits. An important issue is that the procedures relate to/from a specified point in space (hence, PinS) and not necessarily directly to/from a heliport. Flying IFR to that specified point in space, helicopters then fly a VFR segment to the intended landing site (subject to VFR minima) - the reverse would be true for departures.

Image: Rob Inglis Photography

This brings up a potentially thorny question: who develops (and, by association, pays for) and owns the procedures. PinS procedures can be owned by either the helipad or heliport owner/operator, or they could be owned by a helicopter operator. There are both advantages and disadvantages, depending on where one sits in relation to ownership, but what is important is that the costs of implementation for HEMS use need to be kept as low as possible - air ambulance services are generally non-profit making charities with limited cash reserves. The costs of implementation are, therefore, the nub of the issue …. but why is implementation such a potentially costly process?

The basic costs of deploying PinS are not that daunting. The fundamental process involves an obstacle survey, procedure design, flight validation and safety case development - okay, there are a few extras maybe, but none of this is difficult. The real (and potentially costly) issue comes from another quarter: the insistence of the UK CAA that all PinS projects (and associated ACPs) must adhere to the requirements of CAP1616. Why is this an issue: well, we need an understanding of the CAP1616 process and how/why PinS is included therein.

CAP1616 was first published in December 2017 and is now on its 3rd edition (Jan 2020), which superseded a much lighter document with less restrictions (CAP725). CAP1616 was designed to give comprehensive “[g]uidance on the regulatory process for changing the notified airspace design and planned and permanent redistribution of air traffic, and on providing airspace information”[2]. This was intended to ensure that there were no legal loopholes or ‘get outs’ when introducing an airspace change; the CAA had had their fingers burnt on some airspace changes and their fear of ‘Judicial Review’ of their decisions became all-pervasive. To an extent, this could be understood; however, for an airspace change sponsor, the CAP1616 process is incredibly cumbersome, time-consuming and, therefore, expensive. For an airspace change that CAA determines requires their approval, the CAA requires the change sponsor to follow the formal airspace change process (seven stages, some of which have more than one sub-step). There are ‘gateways’ at four points in the process. At each gateway, the change sponsor must satisfy the CAA that the sponsor has followed the process correctly before the application can move to the next stage in the process. This has proved cumbersome, which is highly influenced by the CAA’s fear of ‘Judicial Review’. Clearly, the process can become prolonged and, therefore, expensive; moreover, whilst not spelt out in so many words, it is implicit in the document that it is directed towards aerodromes and regulated airspace, i.e. airspace where the changes will be published and included in the UK AIP.

To reiterate, PinS relate to a point, after which a visual/VFR segment is conducted. Generally, HEMS PinS will be in

uncontrolled

(i.e. Class G) airspace and the procedures will not be published. Why, therefore, are PinS procedures being subjected to the strictures of CAP1616? The answer could be simple: because the CAA has decided so. Surely, the logical supplementary question must be: why?

GNSS procedure implementation has become widespread over the last few years, and most commercial licensed airports (UK and globally) have been enthusiastic in deploying them; however, the capability and benefits of GNSS are most certainly not confined to this sector alone. The CAA acknowledged this and developed a policy for the promulgation of GNSS IAPs at unlicensed aerodromes, which was detailed in CAP1122 [3]. Several smaller aerodromes that had hitherto been unable to offer instrument procedures suddenly saw a great opportunity for operational benefit and commercial expansion, which resulted in a number of these aerodromes sponsoring CAP1122 projects. Unfortunately, CAP1122 gave scant direct reference to PinS, but at least it provided a framework that could be adopted to enable PinS implementation. Sadly, the CAA got ‘cold feet’ with the CAP. There were many stories as to why CAA backtracked, but it was never satisfactorily explained and CAP1122 was subsequently withdrawn in 2018. The GNSS implementation cause (including PinS) suffered a near-fatal blow. The clamour for PinS has not abated, however, and there remains a strong desire among rotary operators for the CAA to produce clear PinS guidance and a pragmatic way forward.

Image: Rob Inglis Photography

The CAA promised that such guidance would be forthcoming (offering that a PinS CAP would be published in Nov 2019), but the wheels of that machine ground slowly; we still await such guidance. In the interim, the CAA decided that, if procedures were to be in the UK AIP or other promulgated aeronautical documents, then the corresponding application must go through the full CAP 1616 process [4]. Thus, it could be deduced - very logically - that if the PinS procedure were not published (i.e. like most HEMS procedures), then PinS need not be subject to the full CAP 1616 process; however, the CAA have never confirmed this (and, yes, we have asked (several times)). The CAA merely offer the acknowledgement that airspace changes can vary hugely in size, scale and complexity; consequently, the CAA can “scale the process appropriately”. CAA go on to state that such scaling “ensures that change sponsors are not deterred by unduly onerous process or information requirements from bringing forward airspace changes which benefit or have a neutral effect on all stakeholders”. Welcome words, but there is no indication what the reduction in the CAP1616 requirements for PinS is and, more anecdotally, the scaling could be too subjective. The advent of a dedicated PinS CAP (or appendix to the extant CAP1616…) would bring welcome clarity for those seeking to sponsor, implement and utilise PinS (and other GNSS procedure applications).

In the meantime, the helicopter community (particularly HEMS) cannot simply sit on their hands.

By delivering life-saving treatment and services, HEMS frequently offer patients the best chance of survival, and the speed at which such patients can be treated and transferred to critical care facilities has demonstrable benefit. At present, this service is dependent on the vagaries of the weather. PinS is a very real solution that can ameliorate the effects of poor weather and enable more flights to be undertaken, but implementation of that solution could be seen to be constrained by regulatory bureaucracy. All stakeholders have a part to play in getting PinS procedures implemented - in particular, the CAA need to prioritise an affordable and practical route to enable PinS deployment and HEMS operators must bring pressure to bear on the regulators to see this through. All parties acknowledge and accept that flight procedure verification and safety and implementation guidance are essential, but a dogmatic adherence to a process that is neither designed for nor applicable to the operation is denying the delivery of a simple and effective enhancement to operational capability.

Aviation and - surely, more importantly - societal needs can only be met by a more pragmatic and proactive engagement from our regulators. We have said it before: the ball is firmly in CAA’s court. I think I know what you mean, but who is applying pressure now (and how)? and to whom…?

If you would like to discuss GNSS PinS operations (or another aviation-related challenge), please feel free to contact us at

info@avigation.co.uk.

#AvigationLtd #HEMS #Helimeds #PinS #GNSS

[1]. A recent HEMS-related article illustrates starkly how HEMS operations are impacted by adverse weather.

[2]. CAP1616, Title Page.

[3]. CAP1122, Application for Instrument Approach Procedures to Aerodromes without an Instrument Runway and/or Approach Control.

[4]. Cited in the record of a related CAA/helicopter operator meeting.